Please click here to opt in to receive via email our Roundup of news and commentary, and click here to view our occasional short video series on executive power.

Confronted with presidential action that threatened its business, Paul Weiss cut a deal with the Trump administration on terms sufficiently attractive to President Trump that he granted the requested relief and rescinded the executive order (EO) targeting the firm. This resolution only partially restored the status quo. On the one hand, the firm can now escape the sanctions imposed by this order, most crucially its ability to represent clients before the government. On the other, it had to enter into an ongoing “engaged and constructive relationship” with the government. It regained normal business by agreeing, for at least the next few years, to a new and abnormal future—one in which the government would partner with Paul Weiss in the administration of firm hiring and pro bono representation programs, and Paul Weiss would be otherwise constrained in the choice of clients it may take on or reject.

The chairman of the firm stated that with this deal the conflict with the Trump administration is “behind us” and normal professional life could resume. He stressed that Paul Weiss had given up very little, merely “reaffirm[ing]” the firm’s principles articulated by one of its founders. Trump thought that there was more to the agreement than that: Firms “want to make deals” because that is what “very sophisticated people” do. And it is in the nature of a “deal” that each side gives up something to gain something, for the mutual benefit of each.

In this post, I will examine what is known about the deal—how it was negotiated, what it provides, and how it may be implemented. I will also consider what we do not yet know, some of which could be as or more important in understanding the significance of the deal. And I will attempt to show that this is a deeply alarming development in the expanding Trump attack on the legal profession.

(Trump on Friday issued a memorandum to the attorney general targeting law firms yet again, this time charging the attorney general with monitoring and taking action against unethical conduct and citing the Elias Law group as its example of the “misconduct” that is “far too common.” I will address that memorandum, and any other intervening government actions against law firms, in the coming days.)

Context

Context here matters. Paul Weiss did not merely negotiate to contain a threat to its business. It did so with the full understanding that the order directed against it was almost certainly unlawful. Only two days prior to the issuance of the Paul Weiss EO, a federal district court concluded that an indistinguishable EO against Perkins Coie violated that firm’s and its clients’ constitutional rights and issued a temporary restraining order on that basis.

The Perkins and Paul Weiss EOs struck at core professional ethical obligations and values in the practice of law. By imposing sanctions for representations described as “harmful activity,” the order was designed to limit these firms’ ability to make independent professional judgments about the clients they take on and the lawsuits they file or defend. Paul Weiss’s alleged failings include bringing a “pro bono suit against individuals alleged to have participated in the events that occurred at or near the United States Capitol on January 6, 2021, on behalf of the District of Columbia Attorney General.” The executive order also held over its target the vaguely alleged misconduct described as inherent in a “global law firm’s” activities, such as its “outsized role in undermining the judicial process and in the destruction of bedrock American principles.” These charges and others, such as actions that “make our communities less safe” and “limit constitutional freedoms,” potentially implicated the broadest range of representations. The government was free under this order to fill in the specifics of what constituted in particular cases any such “harmful” legal services Paul Weiss provided to its clients. And, as in the Perkins Coie case, it further imposed responsibility for past associations with lawyers no longer with the firm who have incurred the administration’s wrath.

Yet rather than take action against the order, Paul Weiss disregarded the lawlessness of Trump’s actions, which is lawlessness of a particularly pernicious kind: punishing lawyers for representing clients or causes personally offensive to this president. Perhaps a different kind of business might sensibly conclude that it should do what it could to placate a hostile administration. But a law firm, in this instance a leading one, is not any kind of business: It is a professional association with obligations not only to its clients, but to the legal system itself.

The Model Rules of Professional Responsibility call on lawyers to recognize that, beyond representing clients, they are officers of the legal system and “public citizen[s] having special responsibility for the quality of justice.” They carry out this responsibility through their exercise of independent professional judgment, and, of particular importance, this “[s]elf-regulation … helps maintain the legal profession’s independence from government domination.” This sentence from the Model Rules is particularly relevant to the Paul Weiss deal with the Trump Administration: “An independent legal profession is an important force in preserving government under law, for abuse of legal authority is more readily challenged by a profession whose members are not dependent on government for the right to practice.”

Paul Weiss’s agreement with the government does not involve a wholesale surrender of its independence, or that of its lawyers. But it accommodates demands from the government that compromise that professional autonomy. This can be seen by closely examining the commitments it made as part of an agreed process of continued “engaged and constructive relationship with the president and his administration.”

The Paul Weiss Commitments

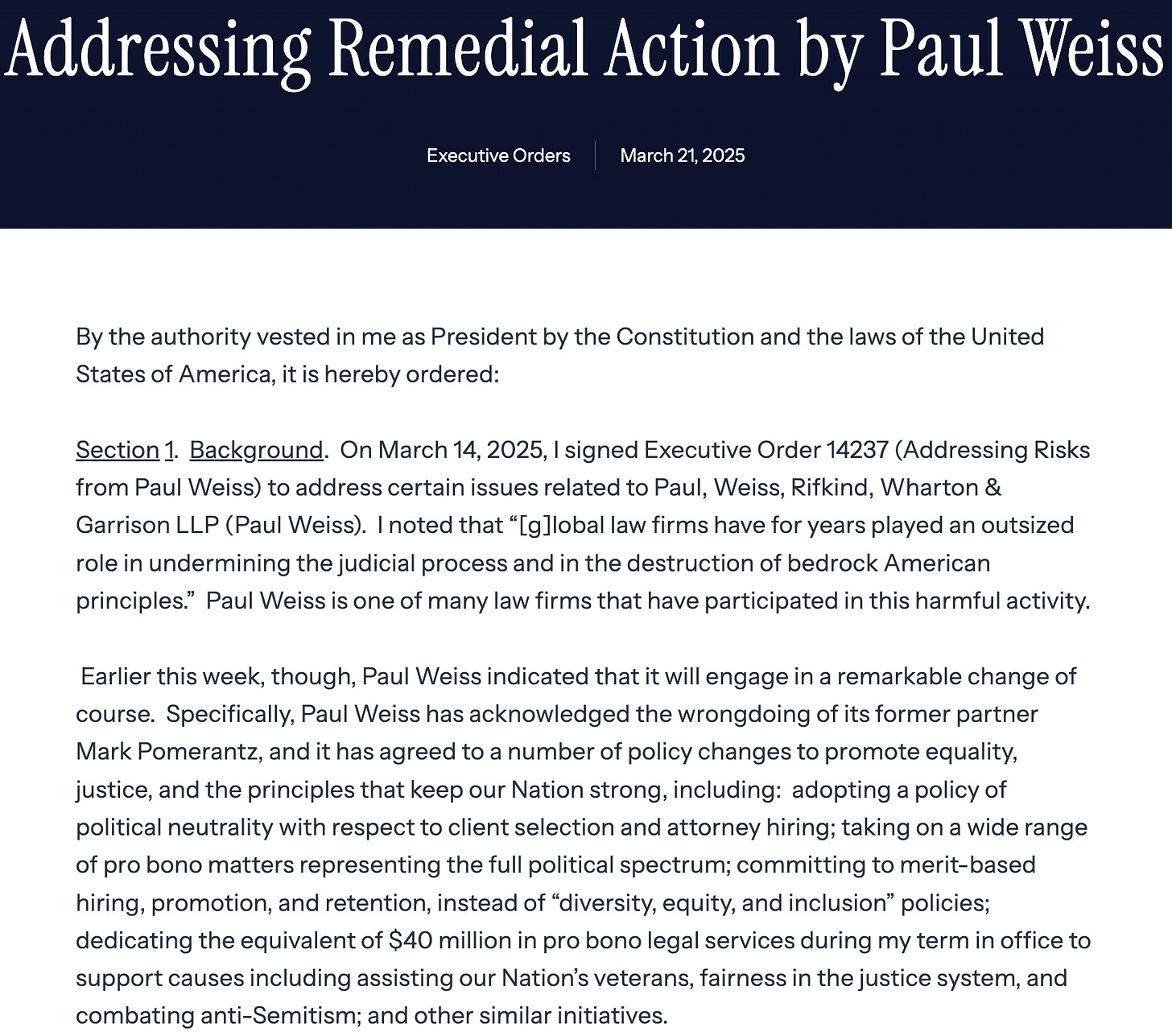

The “engaged and constructive relationship” to which the firm has committed encompasses specific initiatives to be undertaken now and into the future. One example is a review of its hiring practices, with an expert to be retained for this purpose within 14 days, as “mutually agreed upon” with the government. Another is the $40 million worth of “pro bono legal services” it will identify, also as “mutually agreed [upon],” “over the course of President Trump’s term.”

Observers have noted differences in President Trump’s and Paul Weiss’s wording of the $40 million pro bono commitment to be executed on a “mutually agreed” basis. Trump’s version posted to social media refers to pro bono support for the “Administration’s initiatives,” whereas Paul Weiss’s statement cites “these initiatives,” such as ones involving veterans and anti-semitism. (More on the differences in wording between these versions below). Either way, the initiatives subject to this $40 million commitment are ones to be otherwise “mutually agreed [upon].” In other words, this is a commitment to the government for an ongoing dialogue that affects the firm’s choice of who will receive pro bono services over the next four years.

Less specific are a series of broadly stated firm commitments devoid of defining content, but with still more troubling implications for institutional and individual lawyer autonomy. The firm agreed it will not deny representations to any client “because of the personal political views of individual lawyers.” This may seem noncontroversial. But assume that a prospective client wishes to hire a lawyer in the firm who is well-suited to a particular matter but who as a matter of conscience does not wish to participate in the representation. If the firm does not insist that the lawyer accept the assignment, does this constitute a violation of the agreement that impermissible “personal political views” not prevent the firm from undertaking a representation? And what constitutes a “personal political view”? Pure partisanship, as in a refusal to represent a particular political party, or the government’s sweeping charge that in the past the firm has violated “bedrock American principles” and thereby made “our communities less safe, increase[d] burdens on local businesses, limit[ed] constitutional freedoms, and degrade[d] the quality of American elections”?

Similarly, how does the firm propose to comply with the commitment to “take on a wide range of pro bono matters that represent the full spectrum of political viewpoints of our society, whether ‘conservative’ or ‘liberal.’” The full spectrum is the widest possible and does not seem subject to any firm exercise of discretion. It seems that Paul Weiss is bound to take any political representation of any kind, and the deal establishes the basis on which the government could demand an accounting of its compliance with this requirement.

A difference in wording between the firm and the Trump versions of the deal bears on one other commitment the firm made: to pursue only “merit-based” hiring. The Trump version states that the firm agreed that it “will not adopt, use, or pursue any DEI policies.” The version released by Paul Weiss does not refer to DEI. On this point, the firm—which has not disputed the language, only left it out of its version—has exposed itself to disagreement with the government over compliance with this DEI-specific element of the agreement. The parties may not only have disagreements about whether firm commitments to diversity in hiring constitute prohibited “DEI.” The term itself is undefined and may carry any meaning that the administration chooses to assign to it.

How these more general commitments will be implemented or accounted for is unspecified. The agreement does not provide for an enforcement mechanism but does anticipate an ongoing engagement over these provisions for the balance of this presidential term. Nothing prevents the administration from calling on Paul Weiss to establish periodically that it has performed its side of the bargain. A deal is a deal.

And it is a deal that brings the government into the heart of firm governance relating to its hiring practices, the implementation of its pro bono programs, and its discretion in the acceptance or rejection of particular potential clients. Decisions on hiring and on the clients a firm takes on are central to its independent self-governance. The deal with the administration does not put Paul Weiss’s troubles “behind” it but rather requires the firm to proceed now to its implementation phase.

It is fair to consider arguments that some have made that Paul Weiss did not itself give up much, committing to do largely what it would have done anyway. Into this category might fall its agreement that the law should not be put to “political” ends. But it is not so obvious that the administration and Paul Weiss will agree in particular cases on what the misuse of the law for political purposes might mean.

For example, the administration accuses the firm and other “global law firms” of “degrad[ing] the quality of American elections.” In the Perkins Coie case, the same attack on election law litigation singles out challenges to “popular” election laws, including voter identification laws. Does the president believe that these representations are for prohibited “political” ends. There’s every evidence that he believes precisely that. Will Paul Weiss now hesitate before taking cases of this kind, out of concern that it may be violating this element of the agreement? This is the fundamental problem with this agreement: Paul Weiss cannot know what it is, in fact, giving up, as the agreement with its ambiguities and uncertainties looms over it for the next four years.

Unanswered Questions About the Deal

There remain unanswered questions about what took place in the negotiation of the deal and the ways the agreement now binds Paul Weiss. The negotiations are certainly not subject to any attorney client or other privilege.

Yet Paul Weiss has been silent about key details. And it has advised its personnel to “refrain from any social media postings or other disclosures relating to the Executive Order or its withdrawal.”

The still unanswered questions include:

Why are the Trump and Paul Weiss statements concerning the deal different, as in the reference in the former, and not the latter, to “DEI policies”? Notwithstanding the absence of this reference in the firm’s version, it appears in both Trump’s Truth Social version and in the second executive order the White House issued after the agreement to rescind the first. Did the firm in the meeting between Trump and its chairman make this commitment but omit it from express incorporation into its own text? Or did the administration add new commitments to the versions released to the public, and, if so, is the firm now acquiescing by silence in response?

As noted above, Trump claims that Paul Weiss committed to spend $40 million on pro bono representations relating to the “Administration’s initiatives.” The Paul Weiss version refers to “initiatives” as “mutually agreed.” Does Trump’s language reflect an expectation that those initiatives as “mutually agreed” must be chosen only from those identified by the administration?

Press reports suggest that the firm of Quinn Emanuel played some role in the sequence of events. According to the Wall Street Journal, Paul Weiss reached out to the firm and a leading partner, Bill Burck, who reportedly indicated a readiness to bring a case against the government over the EO in the event that Paul Weiss took that route. If this is true, it would have been a remarkable move. Burck is the ethics advisor to the Trump Organization, responsible for reviewing investments and other transactions for potential conflicts of interest. He also represents Mayor Adams before the Trump administration. It is surprising that Burck would have entertained the possibility of a lawsuit challenging an executive order of the same president whose finances he has a hand in managing or advising on. More plausible is the report that Paul Weiss looked to Burck for help in brokering the deal with the administration—perhaps because, as a consequence of his role in Trump’s personal finances, Burck might have special influence with him. The question of Burck’s role is a fair one in this presidency, where the line between the public and private domains seems hard to discern, if it has not reached the point of vanishing altogether.

Other counsel close to the president—personal counsel in an ongoing matter—participated in the negotiation of the deal. The firm of Sullivan and Cromwell is representing Trump in his appeal from his conviction in the Bragg case. The Wall Street Journal reports that in the course of the meeting with Karp, Trump called the firm co-chair, Robert Giuffra, and asked for his views. The Paul Weiss executive order had assailed the firm’s association with the Bragg prosecution, focusing on a former partner’s, Mark Pomerantz’s, membership on the prosecution team and his public criticisms of the district attorney’s early disclination to bring charges. Given this background, which highlights the retaliatory motive for the order, what role may personal counsel have had in the drafting of the executive order, and in advising on the specifics of the deal?

Conclusion

Paul Weiss made its deal, concluding, its chair has said, that it might not “survive a protracted dispute with the Administration.” Other firms will certainly take notice, as will the administration, which now has cause to believe that similar negotiated deals are on the table. Some might think that Paul Weiss did what any business management might do, in the face of an extraordinary threat. Law firms, however, are a particular kind of business, a professional association, and it is hard to imagine that the damage done to the profession by this deal won’t prove worse than the threat from the federal government that it was meant to contain.