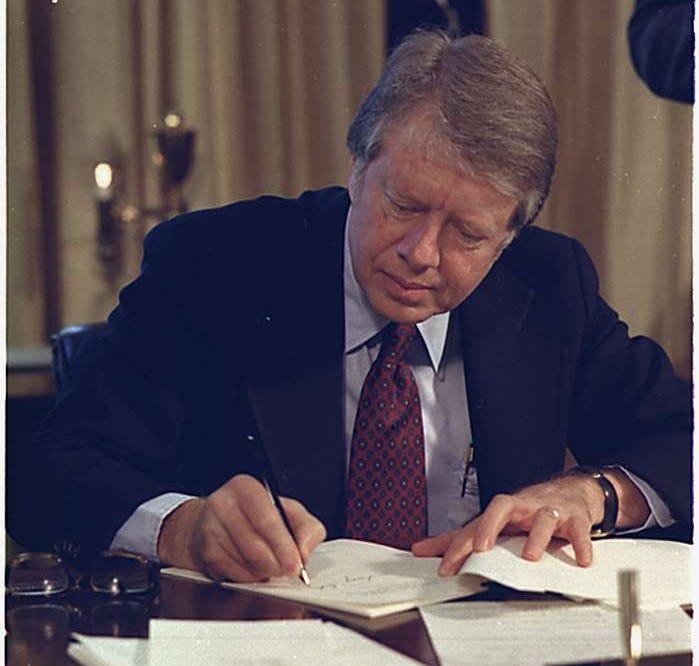

The passing of Jimmy Carter at the age of 100 has refreshed a respectful, but familiar line of critical line commentary: a weak one-term president, followed by a marvelous post-presidency. As an admirer (who also worked briefly in the Carter White House on passage of his energy program), I count myself among the dissenters who believe that Carter had a remarkable and underestimated record in foreign and domestic policy. But I dissent even more strongly from the misguided, conventional picture of a president who was not up to the office but whose reputation was somehow saved by his good work afterward, in his role as “post-president.”

Carter was up to the office, fairly considered, and then some. In four years, Carter did what he pledged to an electorate badly bruised by Watergate: he instituted an honest government to be guided by high policy, not low politics. He made worthy appointments to high positions, made politically costly decisions for the nation’s long term benefit (inflation controls), did more than many who came before and after to reset Middle East policy, established major environmental protections, facilitated a number of important laws and norms (such as a federal ethics law, presidential tax disclosure, and inspector general laws) to render the presidency more accountable, and balanced great power responsibilities with human rights commitments. Like any president, he was held accountable—fairly in some ways and unfairly in others—for tough times, such as the Iran hostage and energy crises, and these developments were damaging to perceptions of his competence. And he struggled to find as president the voice and style as powerful as those that distinguished him as a candidate who came out of the blue to win first his party’s nomination, then the presidency. Still, what he accomplished in his one term seem to me very substantial.

Yet, on the whole, Carter is now hailed for what he did after, not during, his time in office. This perspective, which is now mostly conventional wisdom, owes much to Carter having lost his bid for re-election. In politics, losers are dealt with harshly, the bad result seen to speak for itself. Maybe part of the blame is put on badly run campaigns, but a large part, too, is the conclusion drawn about a presidency from the raw fact of voter rejection. And then even the virtues once attributed to a president can be reconsidered, as in the case of Carter whose known stubbornness in doing what he thought was “the right thing,” politics be damned, has been re-evaluated as self-defeating naïveté.

This performance rating is notable for its underlying assumptions. Presidents have hardly taken their oaths when we begin to hear first-draft assessments of their “legacy.” This legacy is tied a judgment of History who will render a verdict on their successes and failures. This is nonsense, of course. There is no godlike History that ten, fifteen, twenty, or one hundred or more years from now will deliver a clear, firm and final grade on how well presidents carried out their duties. We and others, now and in the future, can argue over these questions, which is fine, and historians will do the same, as they do all the time in histories pronounced “definitive” only to be followed by others characterized as “revisionist.” But this is a parlor game.

So, while Jimmy Carter’s time in office merits consideration as a good presidency, there can be no definitive view on that, not in the lifetimes of those who survive him nor in those of the generations to follow. Narratives and judgments will vary widely across time. There will be differences over particular episodes or chapters in the 39th president’s life and public career, and, inevitably in the irresistible parlor game, over his rightful place or ranking in the estimation of the audience at any one time for these kinds of claims. These differences will be shaped by times and tastes we have no hope of predicting or projecting now. The presidential historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. noted that the “vicissitudes” of presidents’ reputations “rise and fall like stocks on Wall Street, determined by supply and demand equations of a later age”. He added:

The reputation of American Presidents is particularly dependent on the climate in which historians render their verdicts. Judgment is very often a function of the political cycle—that perennial alternation of private interest and public purpose which characterizes American political history. Presidential reputations decline as the opposing mood takes over, only to climb again when the original mood regains the ascendancy.

And these “reputations” will not just “rise” or “fall.” The reasons for this movement, up or down, are unknowable.

The rating game will continue to be played, but it is far from harmless sport. We should not want presidents, in this office bestowing extraordinary powers, to worry about what it takes for them to build their enduring “legacy,” or how History will come to judge them. It is futile exercise and can only exacerbate the dangerous assumption that the best president is the most muscular and dramatically impactful one—and therefore the most likely to overstep constitutional and other boundaries to leave an indelible imprint, or so it is imagined, on future generations. A little humility would be healthy for the institution. When I was President Barack Obama’s White House counsel and attended policy debates, nothing seemed more out of place, or more frustrating, than a staffer’s occasional plea that the course chosen be “on the right side of history.” I don’t recall that an advocate for this prescient bit of policymaking was ever asked to explain how the President could divine the “right side.”

And we don’t need an institution or an expectation of a “post-presidency.” Certainly, presidencies who wish to continue to serve their country can be admired and applauded for doing so—so long as they don’t complicate the ability of those holding the office to be the only “president” at any one time. And their cooperation in preserving the historical record of their tenures is vitally important. But they can choose to go largely quiet in the years after they leave office and that should be fine, too. The greatness that attaches to the office need not rub off forever on its occupants.

It is unfortunate that Carter’s extraordinary years of service at home and abroad after his presidency ended has allowed critics of his presidency to seem generous. “Not a good president, but…” This, I think, gets it all wrong. We may disagree about his presidency, but more negative assessments need not be excused, and the criticism tempered, by pointing to a model post-presidency. What Jimmy Carter did after 1980 deserves recognition but not because he was a model “post-president” but because he was a very good and decent man.

That is the far higher compliment and more certain to endure.