The Meme Coin Is Just the Beginning

The Market for Foreign Government Business Under Trump's New Ethics Policy

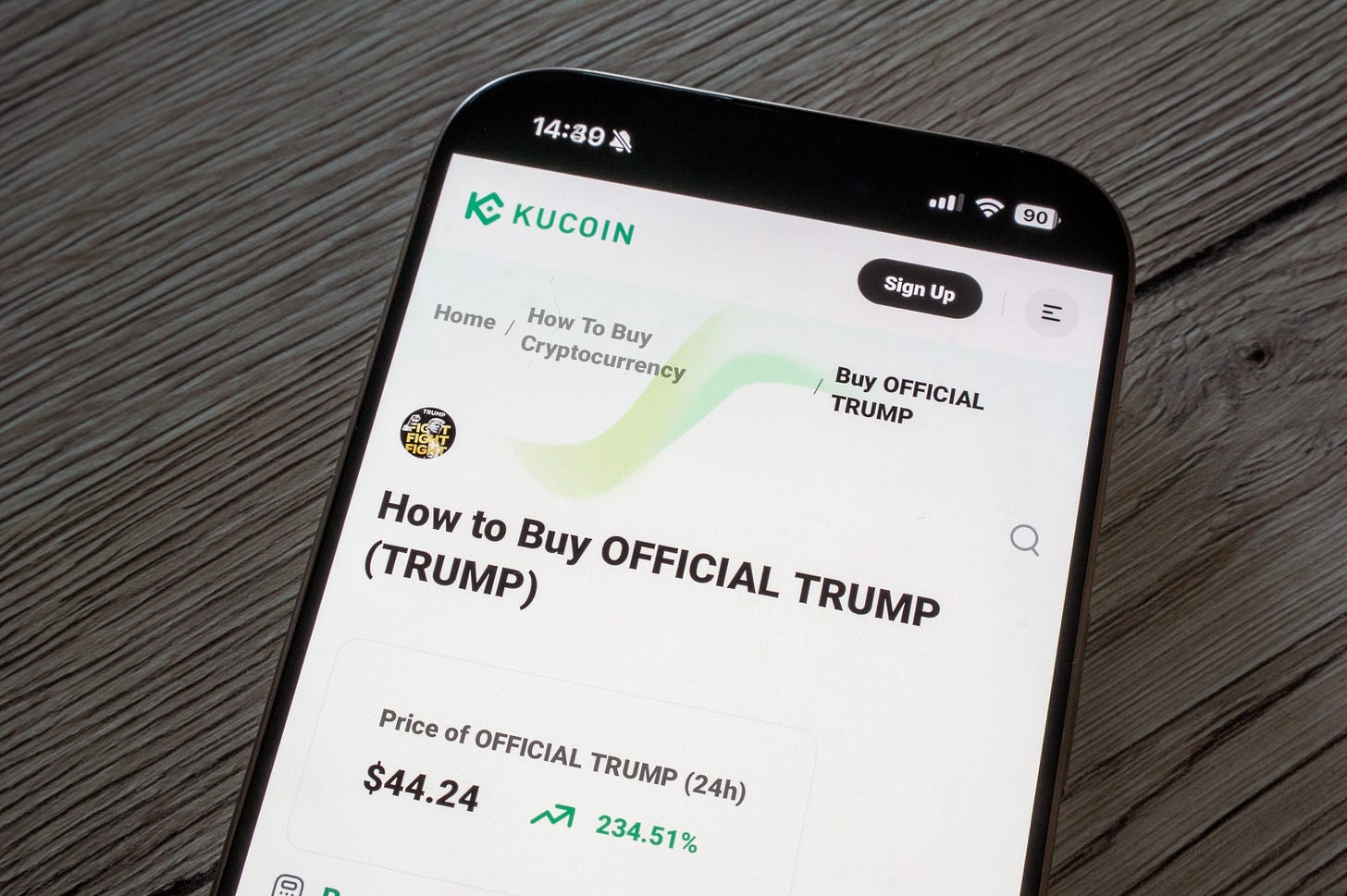

President Trump’s new meme crypto token has dropped from its pre-inaugural highs and in recent days has been valued at only $ 29 billion, a fall of 60 per cent from its peak. Eighty percent (80%) of the tokens are owned by CIC Digital LLC, an affiliate of The Trump Organization (the holding company for the Trump business empire), and Fight Fight Fight LLC, which is co-owned by CIC Digital. The Wall Street Journal Editorial Board recently noted the “flashing-red” conflicts of interest problem in this venture: “A business or foreign official with interests before the federal government might seek to curry favor with Mr. Trump by announcing plans to buy millions of his token to pump up the price. Or, worse, whispering to Mr. Trump that he’s made the purchases, since crypto holdings aren’t disclosed.”

Ten days before Trump’s second term began, The Trump Organization adopted a conflict-of-interest policy for Trump business interests that permits not just the meme coin form of conflicting interests, but all manner of serious conflicts in business dealings with foreign business interests. Trump’s first term also involved a controversial and permissive ethics policy, but that policy still committed in principle to eschewing foreign business transactions by Trump entities. The 2025 policy, set out in a “White Paper” released by the President’s personal counsel, has attracted press attention for lifting the previous constraint on transactions with private foreign business. But there has been far less attention to the ways in which it opens up a bonanza of opportunities for foreign governments, and for foreign government-connected enterprises, to influence the president and to enrich him while in office—and because he is in office.

Trump 1.0

A president by statute must make a personal financial disclosure but otherwise is not bound by the conflict-of-interest laws that Congress has enacted to govern the executive branch. But as Antonin Scalia said when he was head of the Office of Legal Counsel, “it would obviously be undesirable as a matter of policy for the President . . . to engage in conduct” proscribed by the conflict-of-interest rules “where no special reason for exemption from the generally applicable standards exists.” Acting on something like this perspective, every president from Eisenhower through the second Bush established a blind trust of various degrees of seriousness for financial holdings (Johnson’s was the least rigorous and Obama did not establish one because his assets were all in mutual funds and bank accounts).

Trump broke from this pattern in 2017. As Jack and I explained in After Trump, the Trump conflict of interest policy for his business interests declined to divest assets or to place his assets in a traditional blind trust managed by a fully independent trustee. Rather, his sons assumed control of the company and Trump purported to arrange his business interests to, as his lawyer put it, “completely isolate him” from management.

The 2017 policy also contemplated that The Trump Organization would not pursue business deals overseas and would track profits from foreign government patronage at his hotel or other properties and repay them to the United States Treasury. An outside ethics advisor, a Washington D.C. attorney, Bobby Burchfield, was charged with reviewing all new company transactions. As he explained, he was supposed to apply standards crafted to ensure that the transactions were shaped by market forces and not the product of “sweetheart deals,” that they would be negotiated “at arms-length,” and that they would not “embarrass or diminish the President or the Presidency.”

The resort to an outside Ethics Advisor supplanted any role for government ethics officials. It was a fully privatized process that did not provide for any public transparency about, for example, the type of deals reviewed or the outcome of the review process. Over the course of those four years, critics charged that Trump violated these tenets by actively promoting his commercial properties, by profiting from foreign business dealings, and by involving himself in the business through quarterly overview briefings the Policy permitted (and other alleged contacts that it did not).

Trump received no legal sanction for these activities, and Emoluments Clause litigation against him failed. The many proposals to develop legally enforceable conflict of interest policies against the presidency during the Biden years got nowhere.

Trump 2.0

Trump was likely encouraged by the lack of legal or political harm suffered in his first-term ethics controversies to adopt a new, more permissive conflicts policy for his second term. The Policy applies to the Donald J. Trump Revocable Trust and The Trump Organization (together with its respective parents, subsidiaries and affiliates). In clear contrast to the 2017 policy, the 2025 Policy contemplates all manner of foreign business deals. And for both domestic and foreign transactions, it retains the role of the Ethics Advisor (this time William A. Burck, Global Co-Chair of the law firm Quinn Emanuel LLP), but limits the scope of his review and authority. The standards that Burck would apply in reviewing deals for conflicts of interest are described in key terms that are ambiguous or undefined in a document only five pages in length, roughly one-third the length and detail of Burchfield’s guide to the process in 2017.

The relatively tepid reaction to the president handpicking an Ethics Advisor to govern his conflicts of interest in accordance with privately designed rules is one large indication of how the post-Watergate-norms have diminished. Even within this privatized framework, the 2025 Policy steps away from the more robust role described for the Ethics Advisor 8 years ago. Under the first-term regime, Mr. Burchfield clearly suggested that he could disapprove problematic transactions or seek ameliorative conditions before a deal could go forward. The 2025 regime describes the Ethics Advisor as simply reviewing and analyzing a specific list of “Designated Actions,” which include those acquisitions and leases, sales and transfers, debt and refinancing agreements, and guarantees that exceed a value of $10 million dollars, as well as transactions with governments. The Policy carefully defines the role as one of review and analysis, without mention of the authority to approve or disapprove—or to make specific recommendations at all.

And the standards that the Ethics Advisor would use for this purpose have been adjusted in meaningful respects and framed in more general terms to give more wiggle room. The 2017 Policy called on the Ethics Advisor to determine whether a potential transaction was “in the regular course of business and/or for fair value.” The 2025 Policy provides that the transaction be “arms-length,” but it does not include a “fair value” standard. In other words, a negotiation could be “arm’s length,” an important term which is left undefined, but the deal arrived at need not meet market standards for fair value.

There is similarly more play in the joints for determining who would be an appropriate counterparty in a transaction with The Trump Organization. Any such counterparty must only be “appropriate,” without more detail on what this might mean. The 2017 Policy required that the counterparty be “an entity of repute,” a “real party in interest” with legitimate sources of financing. It also required its advisor to look “beyond just the value of the deal” for any suggestion of an intention to exploit the presidency for commercial gain, and it expressed in express terms the goal of protecting against potential embarrassment to the President or the Presidency. These specific concerns have been replaced in the 2025 policy by an undefined expectation that the advisor would examine transactions for “conflicts of interest and similar ethical concerns.”

In short, the 2025 Policy updates the 2017 policy, and not for the better. Of course, we might never know whether it is better or worse in practice, since the Trump Organization will not provide a public accounting of what the Ethics Advisor has reviewed, much less the outcome of any such review. And should any transactions somehow become public, the relative absence of specification in the conflict of interest standards in the 2025 policy might make it hard to say with certainty whether the policy has been meaningfully applied.

Taking all aspects of the Policy into account, it permits a wide range of transactions laden with the potential for conflicts: virtually everything is on the table. By its involvement in crypto currency, the Trump Organization has shown that it does not view itself as limited to the core business pursuits of “world-class hotels, luxury residential real estate, top-tier buildings, championship golf clubs, merchandise and entertainment, and event management.” Nor does the Policy rule out any category of counterparty to a deal, except to indicate that it should be “appropriate.” Nothing in the policy would prohibit the company from considering transactions with counterparties having a direct or indirect interest in federal government policy—as it has done the case of crypto.

And within the room carved out for potential conflicts, The Trump Organization does not limit itself in the purchase of equities. It carves out from the Ethics Advisor’s review the acquisition of any “publicly traded debt and equity securities.” It could buy stock in pharmaceutical, defense, telecommunications and other companies with major interests in the Trump Administration policy. The Ethics Advisor—to the extent that it would make a difference—does not “review and analyze” these stock transactions.

Transactions With Foreign Governments

That the standards have changed is evidenced not only by its allowance for overseas business dealings, but by the treatment of transactions with foreign governments. The policy prohibits “new” foreign government transactions, but with two key provisos.

First, the prohibition applies only to “material” transactions or contracts with foreign governments. The term “material” is undefined. Evidently, some deals not deemed non-material would be permitted.

Second, new “Ordinary Course Transactions” with foreign governments are permitted, and they are not among the transactions subject to the Ethics Advisor’s review and analysis. These “ordinary course transactions” are specifically not included among the “Designated Actions” subject to this review process: they are an exception.

This exception allows the Trump Organization over the course of the presidency to do the following in dealings with foreign governments, in the precise language of the Policy:

“[R]enewing, extending, amending, or modifying the terms of any existing contracts.”

“[F]iling and/or renewing any patterns, trademarks, copyrights or other intellectual property”

“[E]ngaging in any other transactions or activities that are normal and customary in the ordinary course of maintaining, operating and managing the Company’s business and commercial interests”

By this definition of ordinary course transactions, there is ample space for foreign governments, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, to work directly with the Trump Organization or an affiliate within the framework of existing agreements in ways highly beneficial to its business interests.

“Ordinary course transactions” are one significant loophole, but the potential for foreign government influence is greater still under the new Policy through the provision allowing for transactions or contracts “with a subdivision, agency of instrumentality of a foreign government that primary engages in commercial activity (such as, but not limited to, a sovereign wealth fund or state-owned enterprise).” This proviso permits the Trump organization to engage directly with foreign government commercial interests. Deals with entities established and controlled by a foreign government potentially implicate all at once that government’s foreign policy, national security and commercial interests. Under the Policy’s terms, the Ethics Advisor must “review and analyze” any particular transactions of this nature, but there is no categorical bar on entering into them. And, as noted, the standards the Ethics Adviser would apply are not detailed, affording him and the Trump Organization substantial discretion in determining whether they have been met.

In considering how much in the way of foreign business the new Policy permits, it’s important to bear in mind that foreign government interests may also lurk behind even the supposedly private overseas business activity that the new Policy does not prohibit or limit. As one expert has noted in the case of China: “Chinese domestic laws and administrative guidelines, as well as unspoken regulatory and internal party committees, make it quite difficult to distinguish between what is private and what is state-owned.” And governments throughout the world are involved in private businesses in a multitude of ways, through grants, loans, tax, referrals, debt guarantees and the like.

A recent and instructive example of this blurred distinction between private and foreign government interests is a $1.5 billion deal that the Trump Organization entered in October of 2024 with Hung Yen Hospitality in Vietnam for a “5-star hotels, championship-style golf courses, and luxury residential estates.” As in many countries, the Vietnamese government is deeply enmeshed in private sector commercial activities, which are dependent on licensing and other regulatory controls. When the Trump Organization entered into this project, the execution of memoranda of understanding was scheduled a month before the 2024 general election in the United States, timed for a visit from the President of Vietnam. One of the signatories to the deal was “The People’s Committee for Hung Yen province.” One month before the election, Donald Trump personally attended the signing and posed for a celebratory photo.

Given the various paths foreign government and foreign government-connected interests can take in contributing to the President’s (and his family’s) wealth, those who are concerned about serious conflicts will take little comfort in one restriction: The Trump Organization will “voluntarily donate to the U.S. Treasury all profits it receives from foreign government patronage...at its hotels and similar businesses.” (And the Policy notes it can only return those revenues from the patronage that “it is able to identify.”)

Conclusion

The new Policy affirms in its third sentence that “neither federal law nor the United States Constitution prohibits any president from continuing to own, operate and/or manage their businesses, investments, and other assets while in office.” In that same sentence, it claims that the Policy aims “to avoid even the appearance of any conflict.”

By this standard, the Policy is guaranteed to fail. The policy strikes a balance, if one can call it that, very much for the financial benefit of Trump and his family. Under the Policy, revenues may flow freely from overseas deals involving both private sector business and foreign government interests. In many cases, it will be hard to tell the difference.