Executive Functions is seeking interns for the summer and fall. See this post for the details. And please send us your questions for the Executive Functions Mailbag using this form.

On March 25, President Trump issued a sprawling executive order on Preserving and Protecting the Integrity of American Elections. The order focuses on the “integrity” of federal elections. It repeats but does not substantiate Trump’s claims that our elections are rife with fraud, including extensive noncitizen voting. The order appears to be setting the foundation for presidential intervention in the administration of elections in 2026 (and beyond). And it does so in a plainly unlawful way by supplanting the states’ constitutional authority to regulate the “Times, Places and Manner” of elections except where Congress elects to prescribe its own rules for federal elections. The Constitution does not confer on the president any share in this rule-setting authority. Already 19 states and other plaintiffs have filed suits to challenge the order’s constitutionality.

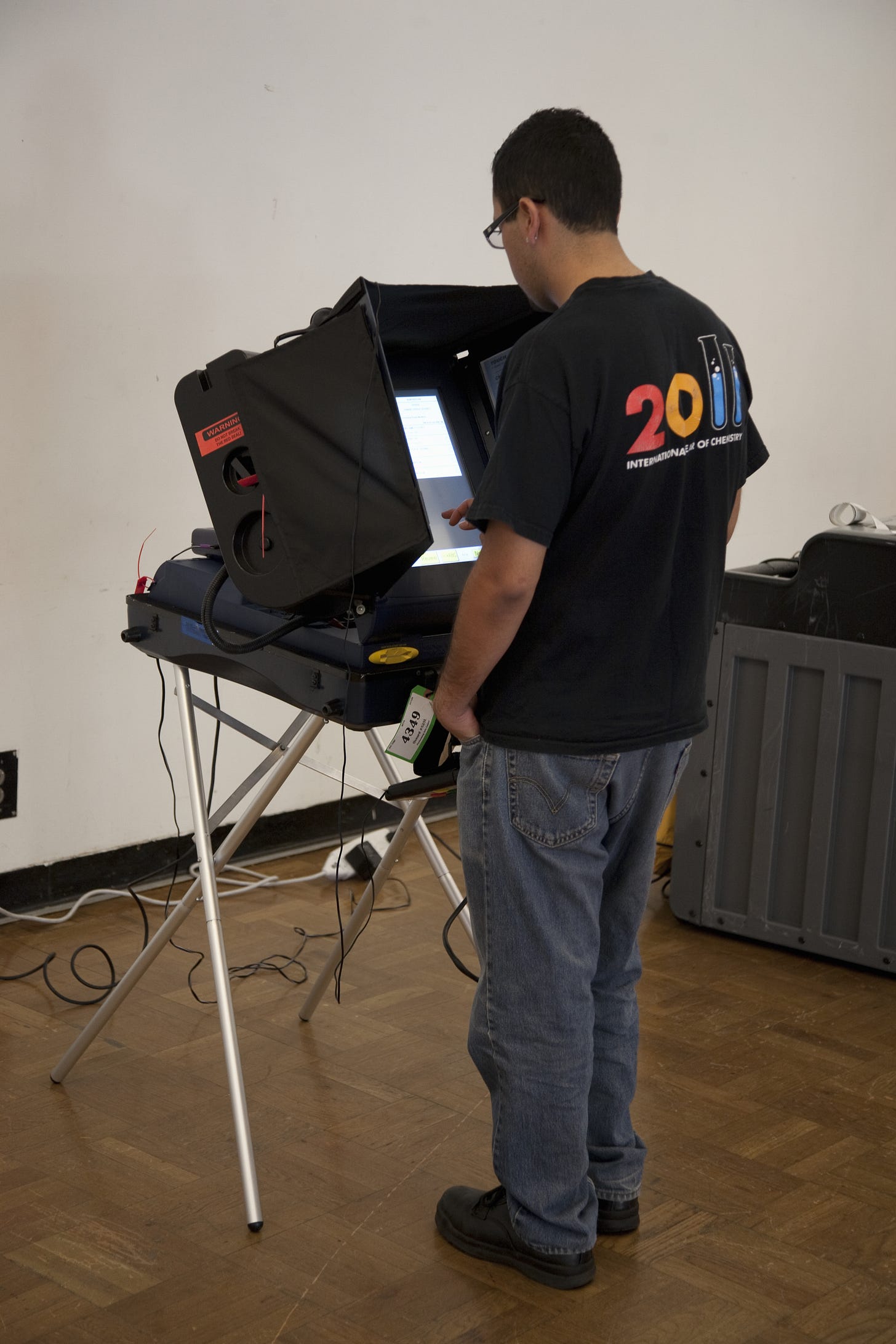

This first in a series of posts on Trump’s voting executive order focuses on one of the likely points of attack in Trump’s elections strategy: refreshing claims from 2020 about rigged or faulty voting machines and providing him with a new argument for seizing these machines in 2026.

The Order

The order, consisting of nine separate sections, can be roughly summarized as targeting these areas or sources of alleged fraud and failed U.S. government enforcement against them: 1) noncitizen voting; 2) mail voting; 3) voting rules including but not limited to state rules that are non-uniform and discriminatory; 4) rigged or flawed vote count machinery; and 5) criminal offenses against election integrity of different kinds, including “unlawful conduct to interfere in the election process.”

To address these issues, the order asserts presidential authority to direct the attorney general to pursue enforcement against fraud and to empower federal agencies to subpoena or otherwise access voting machinery and voter lists to support this enforcement program. Although not a federal agency, the Department of Government Efficiency is also provided a role, “in coordination” with the Department of Homeland Security, in reviewing for accuracy state voter registration lists and voter maintenance activities.

The order also purports to exercise presidential control over an “independent agency,” the Election Assistance Commission (EAC), established under the Help America Vote Act. The EAC’s primary statutory mission is to support the states in their administration of elections. For this purpose, it disburses funds and provides a clearinghouse for advice and support on matters such as cybersecurity protections and technical standards for voting systems. The EAC is also responsible for the design of the “Federal Form” for registration for federal elections, which has involved it in controversies over the adequacy of protections against non-citizen registration. Trump’s order directs the agency to take specific actions and to condition funding for the states depending in part on their compliance with this directive.

Trump has claimed authority over independent agencies more generally, in an executive order that provides that what he refers to as “so-called independent agencies, shall submit for review all proposed and final significant regulatory actions to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) within the Executive Office of the President.” While Congress did not give EAC commissioners “for cause” removal protections, it did designate the agency as “independent” and established a bipartisan structure in which no political party could command a majority of its four members and the parties’ congressional leadership have a role in recommending appointments.

This structure reflects the election-related, and therefore politically sensitive, nature of the EAC’s mission. Any president who sought to assume control of the agency and direct its actions would vitiate the partisan balance in disregard of the core design of the agency. Since the issuance of the executive order, election law experts have argued, as have 19 states and others filing suit, that the president lacks the authority to direct or control the commission. (I will address these constitutional issues in a future post.)

Among the targets of this executive order is voting machinery. The president directs the EAC to “improve the security” of voting machines in use throughout the country. Federal law requires voting machinery to meet minimum standards, such as affording voters the opportunity to review the votes they intended to cast and to correct any error before finally casting them. In addition, the EAC develops and administers Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSGs) with additional technical standards that states may adopt and that, if used, may be certified as compliant by the federal government. Now, under the Trump executive order, the EAC is directed to “amend” the VVSGs within 180 days, and to “issue other appropriate guidance establishing standards for voting systems to protect election integrity.”

With one exception, the order does not state that the guidelines are defective or inadequate. The order directs an amendment of the guidelines to prohibit the use of a ballot “in which a vote is contained within a barcode or quick-response code in the vote counting process except where necessary to accommodate individuals with disabilities.” But the order leaves otherwise unspecified what the revised guidelines should address, or the content of “other appropriate guidance” required to “protect election integrity.”

Moreover, the order calls for review and “if appropriate” re-certification of the machines under new standards within six months. Of critical significance, the order requires rescission of federal certifications granted under previously issued guidelines.

While states are not required to adopt the guidelines, some do, as provided for under state law. The EAC staff reviews guidelines annually with the goal of modernizing standards, but the issuance of new guidelines, which requires years of work, does not involve the repeal of earlier ones. The most recent guidelines, VVSG 2.0, do not displace VVSG 1.0, and machinery certified under 1.0 continues to meet the requirements for federal certification. There has been no evidence of purposeful rigging or hacking of machines, or system flaws, that have affected election results.

Implications and Scenarios

Now that Trump is asserting control over the EAC, he has positioned himself to supervise any amendments to the guidelines and, as in the aspect of the order prohibiting barcodes—to direct or manage specific content. This claim will be contested in the courts, but even assuming that the president has the authority to take any such action, it cannot be accomplished as directed. Election officials around the country have objected that the order, if taken at face value, cannot achieve its declared objectives. There is not yet machinery on the market that can be certified under even VVSG 2.0, much less a re-worked version produced under this order. Even if machinery were somehow available, election jurisdictions lack both the funding to purchase new voting equipment and the time needed to train staff to use it.

Why then would Trump issue an executive order without any conceivable practical effect? A plausible answer is that he is building the unsuccessful case he made against the machines in 2020—including the case he considered then, and could again next year, to support seizing them.

In the challenge to the 2020 election, President Trump and his legal team alleged that voting machines manufactured by Dominion Voting Systems were controlled and influenced by foreign interests and falsely tabulated votes for Biden over Trump in a massive act of foreign interference in the election. Other voting technology companies, such as Smartmatic, were also cited as complicit or involved in this machine-based fraud. Trump pressed administration officials for legal authority he could claim for the seizure of the machines. At least two drafts of an executive order for seizure were prepared. One such draft, dated December 16, 2020, cited various constitutional and emergency authorities for seizing machines, machine software, and other voting equipment alleged to have been involved in foreign election interference.

Officials within his administration objected to both the claims of machine fraud and presidential authority to carry out the seizure. A group of high-level state and federal election officials issued a statement that the election was “the most secure in American history” and that “[t]here is no evidence that any voting system deleted or lost votes, changed votes, or was in any way compromised.” The director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, Chris Krebs, posted that statement on social media. Trump then fired Krebs.

Just this month, Trump took one more action connected to this history which supplies additional background to the new elections order and its objectives. On April 9, Trump issued an executive order stripping Krebs of his security clearance and subjecting him to an inquiry into his “activities as a Government employee.” His alleged offenses during government service included his having “falsely and baselessly denied that the 2020 election was rigged and stolen,” including “inappropriately and categorically dismissing … serious vulnerabilities with voting machines.”

In sum, the new 2025 order restates Trump’s 2020 claims of election rigging achieved through compromised election machinery. In challenges to the 2026 elections, it could help create uncertainties about the outcome and support demands for remedies—including machine seizure.

On one theory, if current certifications are rescinded and machines now in use are generally discredited, state legislators and election officials will be pressured to move to hand counts of ballots. Both Democratic and Republican election officials and other experts routinely warn that hand counts present demonstrably higher risks of inaccuracy. They are also time consuming, and delayed results breed suspicion.

The order may support in other ways a 2026 challenge based on new allegations of machine fraud.

Consider the worst case, where the president does successfully direct the EAC to promulgate new standards on this schedule. Because the standards cannot, as a practical matter, be implemented because of the lack of machinery, funding, or administrative capacity, the president has a ready-made claim against an election he is contesting. His storyline would be simple. Machines don’t meet standards, and all previous certifications have been rescinded: The election was therefore run on unreliable machines associated with fraud.

In this situation, the president and his political allies may again consider issuing a version of the 2020 draft executive order. On the basis of the constitutional and statutory emergency authorities he cited, now supplemented by this most recent order, he could direct in some form the remedies provided for in that draft: that the secretary of defense “seize, collect, retain and analyze all machines” and provide a “final assessment” within 60 days to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI). As provided in that draft, the DNI would then report to the president and designated members of his cabinet. The order also called for the appointment of a special counsel who, on the basis of the assessment provided, would “institute all criminal and civil proceedings as appropriate.”

This kind of machine seizure would have a range of catastrophic effects on the resolution of and public confidence in the elections. The precise way that the administration could use this action and related “assessment” of the machines is at this point obviously speculative. But it is not hard to see their attempted use as “evidence” in election contest or recount proceedings in the states and in challenges brought directly in the House. The courts at both the federal and state levels would be flooded with lawsuits challenging the seizure. Of course, the government’s action and any “assessment” it provided would have no credibility across a vast swath of the electorate, even if potentially cheered by the “stop the steal” wing among Trump’s most ardent supporters. The word “democratic crisis,” so overused, would appropriately describe this state of affairs.

If, however, the lawsuits now underway prevent the implementation of the new order, the argument may shift to the claims that Trump sought to protect the election, through enhanced security of the machinery, and Democrats and liberal groups sued to stop him. And if the lawsuits are successful and the recent past is any guide, blame may fall as well on “Radical Left Judges.”

In any of these cases, the executive order lays fresh groundwork for an attack on the outcome of elections that involves claims of compromised or errant voting machinery.

Conclusion

To read this executive order as evidence of planning for an attack on the 2026 elections is not to indulge in undue alarmism. The history, context, and express terms behind this order justify concern. In any event, I have hoped to provide enough on which readers may reach their own conclusions.

This much is clear: Trump does not accept that he lost the 2020 presidential election, as he restated again in his Easter message wishes to, among others, “all of the people who CHEATED in the 2020 Presidential Election.” Trump continues to insist that he was the victim of fraud and that the voting system, including the machinery in use throughout the country, remains susceptible to rigging yet again. He tried four years ago to do something about it in a bid to remain in office. He failed because the lawyers and officials then in place in the White House and key departments and agencies stood in his way. It is far from clear that this time there is anyone there to take that stand.