Why is the Trump Administration Weakening "Foreign Influence" Enforcement?

The questions of personal pique and financial self-interest.

Note to Readers: We had originally planned to post on Executive Functions every Monday, but given events since January 20 we will going forward adopt a more flexible schedule so we can better track developments. We will continue to post at least once each week.

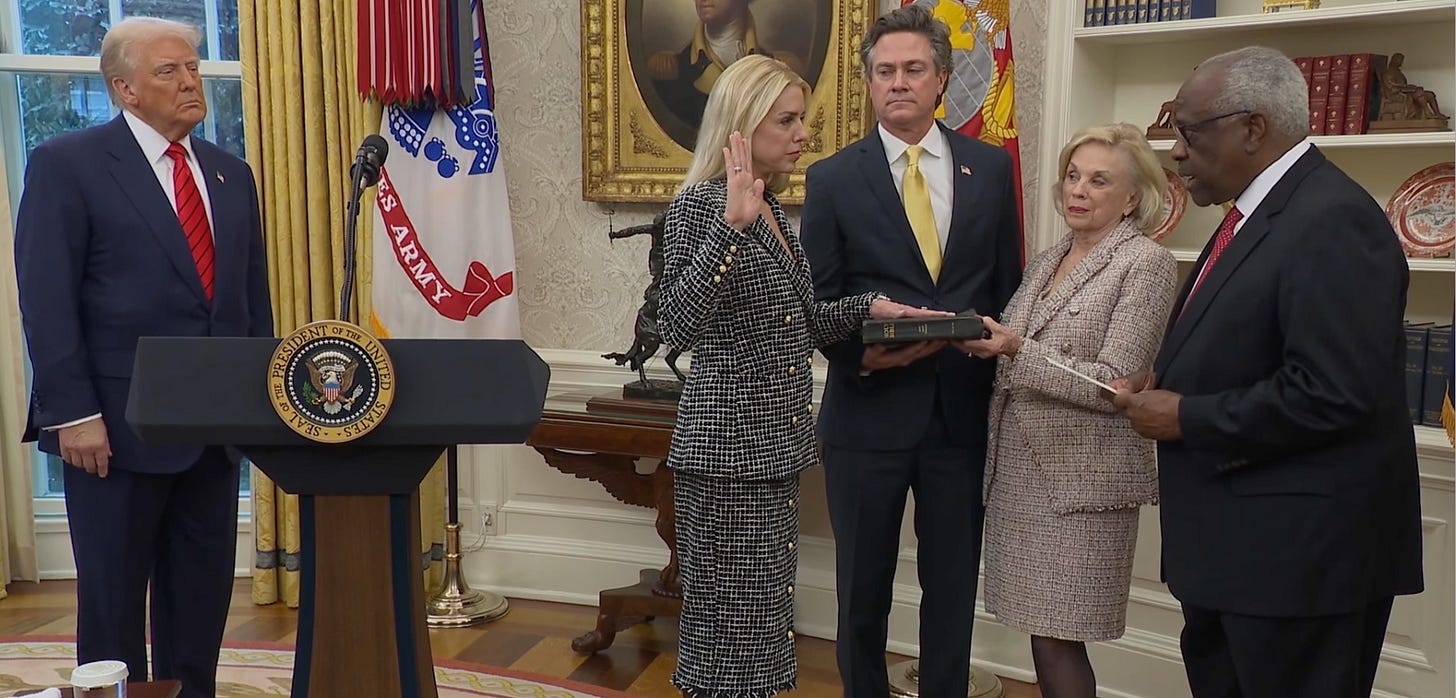

On her first day in office, Attorney General Pam Bondi disbanded the Department of Justice’s Foreign Influence Task Force and sharply cut back on criminal enforcement of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA). The most prominent critical reaction to these moves was that the Trump Administration was “inviting” foreign interests to launch with impunity election interference and other influence campaigns in the United States.

This legitimate and compelling concern, however, does not exhaust the factors that might have affected this president’s policy choices. This post focuses on two other considerations: Trump’s personal pique and his financial self-interest. Questions of motive or intention are never easily resolved. But there are telling indications that more is at work in these first-day DOJ directives than the administration’s changing law enforcement commitments and priorities.

Background

The Unit that Bondi closed was established by Federal Bureau of Investigation Director Christopher Wray in 2017 to “identify and counteract foreign influence operations targeting the United States” through election interference and in other forms. FARA is one tool for addressing these foreign influence issues. It requires registration and disclosure by those acting on behalf of foreign governments, businesses or other persons to influence U.S. policy. Violations of the statute are subject to criminal penalties, including both fines and imprisonment, and to civil enforcement by the attorney general who is empowered to sue to compel compliance.

For the better part of its history, FARA was not the subject of active enforcement. The 1938 law acquired high visibility in prosecutions brought by Special Counsel Robert Mueller related to Russia interference in the 2016 US elections. Among other FARA prosecutions, Mueller brought FARA charges against former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort, Manafort’s deputy and business partner Rick Gates, and Trump’s former National Security Advisor Mike Flynn. Mueller brought seven FARA criminal enforcement cases in all, as many as the Department of Justice had filed from 1966-2015. Since then, DOJ has far more aggressively pursued other violations of this “once-obscure” statute and toughened enforcement more generally in guidance provided to the regulated community.

The Question of Motive

One indication of motive is the “baby-tossed-out-with-the bathwater” feature of these policy changes. Bondi does not invoke the fair questions that have been raised about the potential problems with DOJ’s approach to enhanced criminal enforcement of FARA. Nor does she say anything about the reality of the foreign interference threat or how it might otherwise be confronted. She simply cites the need to “address more pressing priorities” than foreign influence and severely restricts criminal enforcement of FARA to “instances of alleged conduct similar to more traditional espionage by foreign government actors.”

This is much more than adjusting FARA down the scale of priorities. In the realm of criminal enforcement, it is taking off the table the law’s concern with the many other ways that foreign governments seek to influence US policy and public opinion beyond “traditional espionage.” And while the Bondi Directive concerning FARA also notes the objective of ending “risks of further weaponization and abuses of prosecutorial discretion,” those risks could be addressed well short of a sweeping de-prioritization of this law’s enforcement.

It is striking that the Bondi Directives break sharply with the bipartisan priority previously assigned to foreign influence activities, including by the new Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, and National Security Advisor, Michael Waltz. Both have previously ranked foreign influence operations high on their list of priorities—that is, before they joined this administration. As Senator, Rubio had “taken a keen interest in countering foreign influence operations.” He cosponsored a bill, the Foreign Agents Disclosure and Registration Enhancement Act, in order to add “teeth to existing law” to protect against influence campaigns. In supporting the bill, Rubio declared that he was “committed to holding accountable those individuals and foreign governments who would attempt to obscure their efforts to influence our government.”

NSA Waltz shared these policy priorities when he was a member of Congress who also served on the House’s Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. He sought then to bring attention to foreign “gray zone” activities by foreign governments, with the “gray zone” generally understood to be hostile foreign government action short of military engagement or outside the norms of traditional statecraft. One such “gray zone” is foreign interference in U.S. elections. These activities, he told one audience, were “often associated with Russia,” but he pointed in particular to this threat from the Chinese government.

On the surface it is difficult to square Bondi’s moves with the views of these two Trump cabinet officials, and with the intelligence community’s assessment that foreign influence is “likely to increase and diversify because of more enabling technologies, the erosion or absence of accompanying norms, challenges with attribution, and perception [to foreign interests] of their advantages.” And it is too easy to suggest that Trump welcomes foreign influence campaigns, such as Russia’s, because he imagines that “inviting” these activities would redound only to his advantage. Iran and China are also “gray zone” actors,” and Trump cannot expect that these foreign influence campaigns would be waged on his behalf.

Trump’s Pique

One plausible explanation for the Bondi FARA Directive is that Trump cannot expunge the bitter taste of what he repeatedly denounced, in tweet storms and other occasions, as the “hoax” and “witch hunt” that he believed were driving allegations and investigations of alleged collusion between his 2016 campaign and Russia. It may have been enough for Trump that former Special Counsel Mueller, whom the president has angrily dismissed as a “Never Trumper,” testified before Congress that Russian interference in US elections was “among the most serious” challenges to democracy he had witnessed over the course of his career, one which “deserves the attention of every American.” Trump’s well-documented fury over these claims from Mueller and others may have counted more than any policy rationale or consequence for the reversal of course on foreign influence enforcement that his attorney general announced.

That pique at various levels of rage and resentment may have powered this FARA enforcement shift is far from fanciful. In his inaugural address, Trump made repeated references to the historic challenges from ruthless adversaries he had to overcome to return to the presidency, stressing his view that “over the past eight years, I have been tested and challenged more than any president in our 250-year history” and that “those who wish to stop our cause have tried to take my freedom and, indeed, to take my life.” He proceeded promptly after the speech, “as one of his first acts in office,” to put his pique on immediate display by stripping his former National Security Advisor John Bolton, the target of Iranian assassination plots, of his security detail.

Trump’s Financial Self-Interest

A second troubling explanation for these policy moves is that they serve Trump’s continuing pursuit of his business interests. FARA contains a key and controversial exemption from its requirements for “commercial” activities, defined as “private and nonpolitical activities in furtherance of bona fide trade and commerce.” This complex exemption basically allows for actions to influence U.S. government policy in support of foreign government owned or controlled business interests but only so long as these activities do not “directly promote [the foreign government’s] public or political interests.” As legal specialists have advised their clients, the question of when this exemption applies is one of the “most frequent” issues before DOJ in FARA enforcement, because “the practical reality is that in many parts of the world, foreign governments and foreign government officials are inextricably intertwined with commercial business.”

I have noted this same point in relation to the extraordinary and permissive “conflict of interest” policy that the Trump Organization adopted for Trump 2.0. It expands significantly the policy in effect in Trump 1.0, affording substantial latitude to the Trump Organization to pursue business deals with foreign partners and counterparties that are connected directly (as in the case of sovereign wealth funds) or indirectly with foreign government interests. As noted in that post, “[Under] the Policy, revenues may flow freely from overseas deals involving both private sector business and foreign government interests. In many cases, it will be hard to tell the difference.”

By gutting criminal enforcement of FARA, the Bondi Directive reduces the legal risks faced by companies like the Trump Organization that interact with government officials to advance favorable conditions for business interests shared with foreign governments, and foreign-connected partners and counterparties. The Directive now establishes as the new focus of enforcement “civil enforcement, regulatory initiatives, and public guidance.” In other words, it amounts to a major retreat from “adding teeth” to FARA enforcement, as once supported by then-Senator Rubio.

As for the “regulatory initiatives” that the Directive leaves open as a policy alternative, it is noteworthy that on December 19, 2024, only a month before Trump took office, DOJ published a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on FARA enforcement. If adopted, it would substantially narrow the availability of the commercial exemption. The Bondi directive makes no specific mention of this rulemaking, and it will be telling if the Department proceeds with it, or abandons it in its current form, or in any other.

The effect of these new policies in removing obstacles to the Trump Organization’s pursuit of foreign business interests is and can only be a hypothesis. But any consideration of this possibility must begin with known facts. First, after his election, Trump adopted an ethics policy that permits the Trump Organization’s active pursuit of overseas business, including commercial ventures connected to foreign government interests. Second, since taking office, his administration has reduced the legal risks of going down this road on several dimensions. While it is still unclear whether this boost to Trump’s business interests is a byproduct of this dramatic policy shift or a factor in its development, the question is a serious one. And the more that disparate policies trend in the direction of supporting Trump’s private business pursuits, the more likely— and plausible— the inference that these private interests are guiding policy.

And it is not the only indication that these interests influenced—or would be foreseeably affected by—the Bondi Directives and other administration policy. Another Directive the Attorney General issued on her first day in office downgraded the priority assigned to corrupt US business practices overseas, such as bribery of foreign officials, as prohibited by the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). A week later, on February 10, 2025, President Trump issued an Executive Order to suspend with limited exceptions FCPA enforcement. The suspension runs for 180 days (subject to case-by-case Attorney General Counsel exceptions), with allowance for another 180 as the attorney general considers “updated guidelines or policies, as appropriate, to adequately promote the President’s Article II authority to conduct foreign affairs and prioritize American interests, American economic competitiveness with respect to other nations, and the efficient use of Federal law enforcement resources.”

However difficult it may be to assess intent, the combined effect of the Bondi Directives and the FCPA executive order is to sharply limit legal risks and issues posed for the Trump Organization’s engagements with government officials both at home and abroad.

Conclusion

The onrush of Trump 2.0 executive orders, announcements, tweets, and reported administrative actions can make it difficult to focus on the fine print and key context which illuminate the less immediately detectible purposes and potential impacts. An example is the new President’s “conflict of interest” policy, which, as I discussed in an earlier posting here, is far more permissive than originally understood and reported. The Bondi Directives on foreign influence, foreign agent disclosure, and corrupt overseas business practices, and the President’s Executive Order directing suspension with limited exceptions of FCPA enforcement, are further examples of major policy shifts that are remarkable enough on their face but may also have been motivated or influenced by Donald Trump’s deeply personal interests—in this case, both his politics of grievance and his pursuit of financial gain.